The Jeffrey Family traces their presence in North America to the 17th century in historical records.

Old Lyme, CT: “We are not extinct, we are very much alive.”

Wigwam Rock at Black Point

In 1998 the New York Times reported:

The Nehantic were one of the most numerous and historically significant Indian groups encountered by European settlers in Connecticut. But by 1870 they were declared extinct by the state. Their 300-acre reservation, which encompassed all of the Black Point peninsula in East Lyme, was sold.

The state promised to respect and preserve the tribe’s burial grounds. But in 1886 the burial ground, too, was sold and desecrated. Much of the Crescent Beach section of East Lyme has been built over it and as recently as 1988, Nehantic skeletal remains were uncovered by new construction (Libby, New York Times, August 2, 1998).

The state promised to respect and preserve the tribe’s burial grounds. But in 1886 the burial ground, too, was sold and desecrated. Much of the Crescent Beach section of East Lyme has been built over it and as recently as 1988, Nehantic skeletal remains were uncovered by new construction (Libby, New York Times, August 2, 1998).

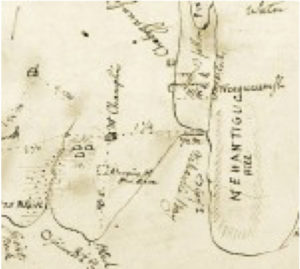

Ezra Stiles‘ map of Nehantic Lands

The article discusses the organization of a group of Nehantic descendants that gather each year. This group has grown, and they hold a multiracial gathering of families descended from the Nehantic/Narragansett tribes in Old Lyme, Connecticut every August.

The group travels to Charlestown, Rhode Island the following day for the annual Narragansett powwow. (The Nehantic and Narragansett tribes merged in approximately 1676.) One of the larger family groups is composed of descendants of Joseph Jeffrey, a Nehantic man born in 1695. The home he built in Charlestown, Rhode Island is on the national register of historic places, notable for its integration of Native and Colonial architecture.

This is Joseph Jeffrey’s house, and the site of Jeffrey’s Mill, on Old Mill Road in Charlestown, Rhode Island.

He served as a primary advisor to Sachem (Chief) Ninigret after the two tribes blended. Research indicates he was likely of mixed race and ethnicity, though this is not certain. His descendants however, are a diverse group of people who variously “appear” and/or identify as Black, multiracial, Native, and white. My spouse and my children number among these descendants.

The following connects to the Joseph Jeffrey page on wikitee:

Racial identity was a crucial factor in declaring the Nehantic tribe extinct. As I dig deeper into archival research I find what, at first, seem like contradictions in census records.

One of my wife’s great grandfathers, born in 1780, is listed on one census as “Indian,” in the next census he is listed as “Free Person of Color,” in the next he is listed as “Mulatto,” and then as an old man he is listed as “White.” Yet these are not necessarily contradictions.

They reflect both racial ambiguity in his appearance, and shifts in census categories for mixed race people that are tied to racial politics, settler colonialism, and capitalism. The Nehantic Tribe was eventually declared extinct based on declining population. This cannot be understood apart from political definitions of racial identity used as justification for removing Indigenous lands. As Nehantics intermarried with free-born and formerly enslaved Blacks, blood-quantum regulations defined them out of their own tribe.

This is a history deeply tied to shifting social understandings of race in the U.S. that have historically served to deny the continued existence of Indigenous peoples in North America. This history also challenges widely held assumptions that slavery was only practiced in the Southern United States.These two genealogical narratives challenge contemporary understandings of family, race, gender, reproduction, and American history. While each family story is specific, I argue that each can be read allegorically, as part of an historical discourse on family and national belonging that challenges partial and homogenous histories that claim to represent the “truth” of the past.

Venture Smith

Venture Smith’s narrative tells us about enslavement in the North. According to Archeologist John Pfeiffer, Venture Smith is related to the Jeffrey family, though the exact connection has not been established.